-

Administrator

In early 1980, Johnson, with no car and no sponsor, was sat in his living room watching the opening round of the 1980 ATCC on tv. In this race, privateer racer Gary Willmington, the first person to race the new XD model, was demonstrating this to be a car which Johnson considered had plenty of potential. Johnson knew then he had to find a way to fund an XD project. When the ATCC visited Lakeside, in Queensland, on March 30, Johnson went and had a good look at Willmingtons Falcon. He knew Willmington was struggling to gain financial support to keep the car going, so offered to buy it. As Willmington didn’t seem too keen, Johnson then set off to find John Harris, who was at the event, with a proposal.

He knew Harris still had the old XC Falcon hardtop left over from 1979, with nobody really interested in buying it. He wanted to buy the XC plus all the spares which came with it, plus an XD road car, into which much of the componentry could be transferred. Johnson had A$32,000 in his private bank account, which was all the money he had. He told Harris he’d give him the 32K, in exchange for the XC and spares, plus an XD road car, and he’d run Bryan Byrt signage on the car for twelve months. The next morning, Harris phoned, agreeing to the deal, provided the motor and gearbox be removed from the XD, and put into the XC, along with removing the XC’s rollcage, so Byrt Ford could sell it as a road car.

In fact, the XD supplied to Johnson was not a new car. It was an ex-Police Highway Patrol vehicle, with 43,000km on the clock, which had been bought at a State Government auction. But that mattered not to Johnson. As soon as he got it back to his workshop, he and his small team tore into it, converting the running gear into the XC. Then they spent every evening, and every weekend, over the next three months, converting that ex-Police car into the race car that would change Dick Johnsons life forever. They beat themselves to death, and were all dead on their feet when the beautiful blue machine, almost completely devoid of sponsorship, hit the track for the first time on July 20, just two days before a local event at Lakeside.

Johnson had lined up some potential sponsorship from the computer company Facom, on the proviso the new car beat the Lakeside lap record, set by Kevin Bartletts Chanel 9 Camaro a few weeks earlier. Johnson qualified on pole, and stormed into the lead, but the speed differential between himself and the slowest cars was such that within a few laps, just as he was gunning for the lap record, he found one of the slower cars right in his path. As he described it in the brilliant Bill Tuckey book, The Unforgiving Minute, “I was on this brilliant bloody lap, that would have blown the old record 16ft in the air, with all that sponsorship hanging on it, and would you believe it... bloody Zoom Zacka did a right turn in front of me in his Gemini, and I planted him. I think I got fined for speeding in the pits, but that cost me $100,000, because Facom put it all in the too-hard basket”.

With little money, Johnson and his team set off for the CRC 300, on August 9, as part of the Endurance series. Against all the heavy hitters, Johnson planted the Falcon on the outside of the front row, next to Brock. Whereas Johnson was scrimping for every penny, Brock was reported to have amassed a budget of around A$400,000 for the season, with the newly created Holden Dealer Team, that was individually funded by several Holden dealerships throughout Australia, rather than General-Motors Holden, and with additional backing from Marlboro and other sponsors. Johnson couldn’t even afford a co-driver for Amaroo, so drove the full 300km on his own. After leading the first 20 laps, his rear tyres began to go off, and he spun, allowing Brock, who was teamed with John Harvey, into a lead they would not relinquish. But Johnson finished an impressive second, and fired a warning shot across the bows of Australia’s top touring car teams.

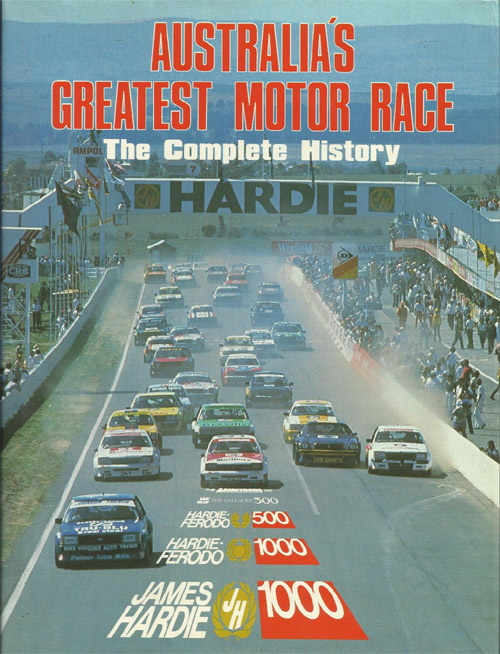

Next stop, Bathurst.

By the time he’d raced the Amaroo event, Johnson was nearly broke. He told reporters at the CRC 300 he’d be struggling to make Bathurst that year. The organisers for the traditional Bathurst lead-in race, the Sandown 500, tried to get him to attend, but he wasn’t interested, partially because he couldn’t afford it, partially because his team were exhausted, and partially because he knew if he could get to Bathurst, he had a genuine shot at winning the big one, and he wanted to take his rivals by surprise. Brock/Harvey blitzed everyone to take out the Sandown 500 in 1980.

In between Amaroo and Bathurst, Ross Palmer called by Johnsons home. Following Johnsons impressive showing at Amaroo, Palmer took in a visit to his accountant, and between them they set aside an advertising and promotions budget for the next twelve months, of $50,000. And Palmer was going to sink the whole she-bang into Johnsons big blue Ford. It wasn’t a budget to rival that of Brock, or several other top teams, but it allowed Johnson to get to Bathurst, and not have to lie awake at night worrying about money. While his rivals could bolt on super-sticky tyres for qualifying, Johnson would have to make do with race rubber, and although he’d be staying in free accommodation, and his crew stayed in caravans at the track, at least they’d be there. For Bathurst, Johnson would have his good mate, and Bathurst veteran John French as co-driver.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote