-

Administrator

Article: Triumph TR-250K

“Peter had finished his design work at Shelby American”, explains R. W. “Kas” Kastner, “and was looking for an effort that would show his ability. I was looking for a chance to show off the name Triumph”. The ‘Peter’ Kas is referring to is Pete Brock, the youngest designer ever hired at General Motors Styling Division when he joined the company at age 19. In 1957, he penned the shape for what would ultimately become the Corvette Stingray, eventually released in 1963, by which time Brock was working for Carroll Shelby, initially running his driving school (he was actually Shelby’s first-ever employee), before switching to, and helping create the Shelby American brand, as Carroll Shelby went into production building the AC/Shelby Cobra.

Although Pete Brock’s earlier roles at Shelby leaned more towards marketing, through designing logo’s, liveries, advertisements, and the like, he would eventually go on to design the highly successful Daytona Cobra Coupes which raced during 1964/65, before branching out on his own in late ’65 to form Brock Racing Enterprises (BRE). By the early 1970s, BRE were running the factory Datsun team in SCCA Trans-Am and C/Production Sports, but the intervening years saw work with Hino and Toyota, using motor sport as one of the key areas to help build their brands in the US.

“Anyway, we bantered on and on about this car several hours every week, on the phone, running cars on my slot track and just hanging around. It was never something that had a direct aim at the time nor was there any device to see it happen. It was always just bench racing talk. Then it happened.

“As Competition Manager for Triumph in the USA, I was sent or was called to Coventry England on many occasions. One Thursday, the call came. We'd like you to be here on Monday. I checked my passport and found it had only a week before expiration so I had to make a deal in downtown LA to get that renewed, make the reservations and gather my wits and wish lists.

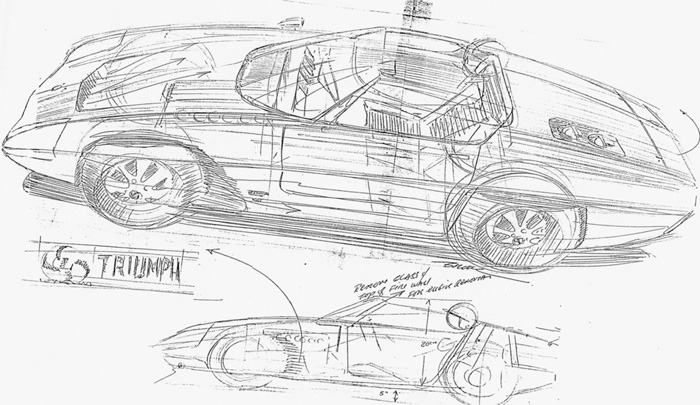

“I called Peter on the phone and told him I was leaving for Coventry. If he could get me a sketch of the car we were talking about I'd make a stand at trying to not only get permission to build it, but also to try and find some budget. In fact the time element was so short that Pete only had about an hour to not only do the sketch but to get it to me in my office in Gardena, California 'cause I was going to be on a plane that AM.

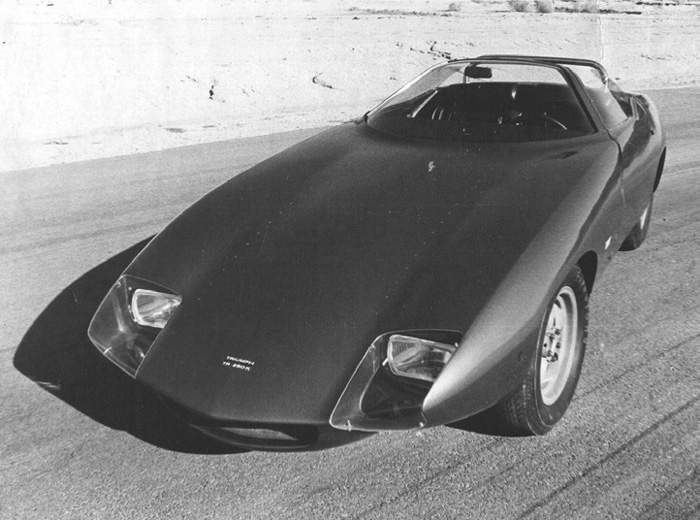

“In about forty-five minutes Peter Brock rolled up to the Triumph offices in Gardena and handed me a rolled up sketch on heavy paper about 18" by 11". I unrolled the paper and saw this really neat sketch of the OUR CAR”. The result of Pete Brocks creative juices was a concept so striking, it could have leapt straight from the screen of the ‘60s Japanese originating cartoon tv series Speed Racer. For a company whose designs still retained a hint of their cottage industry roots (and which many of their customers still expected), this was a world away from their standard fare, and quite futuristic. Heavy emphasis was placed on aerodynamics, or, more specifically, of slipping through the air far more efficiently than a standard TR model. But overall the design was one that embraced the future, not the past.

-

Administrator

Kas was not only a Triumph employee, he was a Triumph enthusiast, and was desperate to inject some excitement into the brand, whose reputation had been built on the back of designing sporting vehicles, aimed at the driving enthusiast. Although never flush with money, even when Standard-Triumph was purchased in 1960 by Leyland Motors, there remained recognition within the company that its sporting endeavours were an important part of its marketing strategy, and the reasoning behind many people buying its cars.

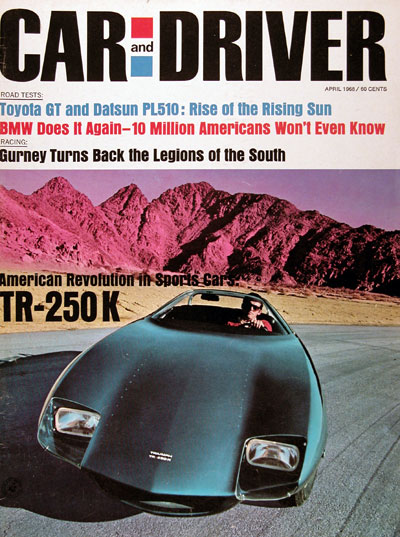

But Kas made sure he armed himself with the best offensive strategy he could, to help sway the company top-brass into giving this concept the green light. So, on his way to England, he stopped off at New York, to visit his good friend, and Editor of Car And Driver magazine, Leon Mandel. Kas showed Leon the concept drawing sketched out by Pete Brock, and asked, “If I get this car built will you give me the cover of the Sebring issue next spring?" After mulling over the proposition, Leon agreed, and Kas now headed for England with Pete’s beautiful concept drawings under his arm, and the guarantee of front page exposure with one of the worlds most influential automotive magazines.

On meeting with managing director George Turnbull, Kas was given the green light, not only to build the car, but to race it in the 1968 Sebring 12 Hour, on March 23, 1968. His budget was US$25,000, which, even in 1967 was completely insufficient. But to Kas, this mattered not, he was an enthusiast, who wanted to see this concept brought to reality. He immediately let Pete know the good news, and relayed the impossibly tight budget they had to work with. Pete then set to work, using his vast array of connections, gathering sponsors, to cover some of the costs.

The Triumph TR-250K (‘K’ for Kastner?), as it was designated, needed to be built on an existing platform, to keep costs down, and to help push through the argument that the car should eventually go into full production. The standard production Triumph TR-250 was built specifically for the US market, itself based on the TR5, but fitted with Zenith-Stromberg carburettors, instead of the TR5’s fuel injection system. A TR4A frame was sourced, along with a TR-250 motor, on which Webers replaced the standard Zenith-Stromberg’s. The motor was then set back 11” in the chassis, for better weight distribution and to allow for the low, sharp nose design.

Mechanical and chassis work on the TR-250K was undertaken by Kas, Jim Coan, and Bob Avery at Triumph’s competition workshop. Pete organised the fabrication work of the sweeping, alloy body, contracting the job to Borth and Rose. Pete also sourced the swept back windshield, incidentally, a Hino Samurai GT item, which he still had from his programs with the Japanese manufacturer. Typically, there were delays, as virtually everything sitting above the chassis had to be custom built from scratch. Kas was coming under increased pressure from the Triumph PR team, wanting to know how the car was progressing, and when it would be ready.

-

Administrator

“We were down to scratches and bites on lots of thing to get the car finished”, says Kas. “Ten people worked all night before the Forum intro to finish the paint and I was tearing my hair out in clumps because the road springs I needed had not arrived and the car was sitting up like a dune buggy. Not the slick looking low racer we wanted”. But through a series of improvisations, and a little ‘smoke and mirrors’, the stunning TR-250K, looking spectacular in its newly applied Dave Kent blue paint work, was unveiled to the press at a new ice hockey palace in Inglewood, Los Angeles, to a great reception.

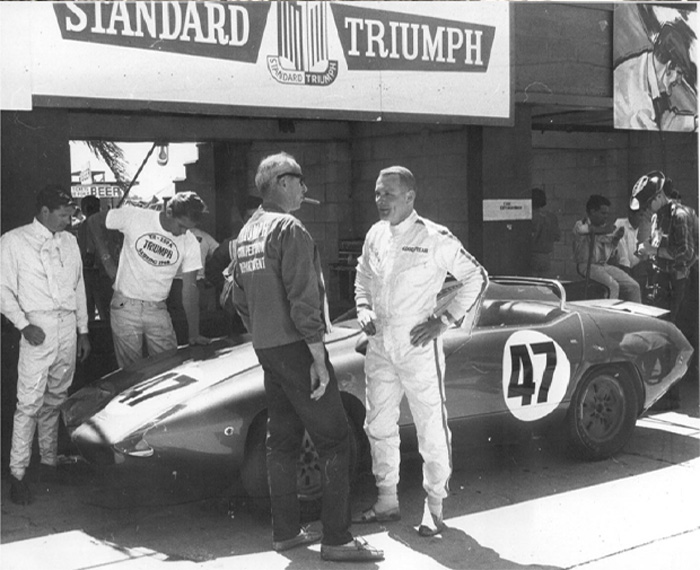

The TR-250K raced just once, as promised, at the 1968 Sebring 12 Hour. The organisers, perhaps a little unsure where the car fit into their line-up, placed the Triumph in the Group 6 Sports Prototype class, in which there were four other entries, all works Porsche 907’s.

With the completion of its build going right down to the wire, the team were essentially forced to do testing of the Triumph at its race debut, at Sebring, which certainly wasn’t the ideal situation. It was entered under the Leyland Motor Corporation banner, with Jim Dittemore and Bob Tullius assigned to the driving roles. “We were testing and tuning the engine at Sebring on a road beside the back straight that gave us plenty of run so that top gear shut-off could be checked for mixture. There was also a kink in the road that was a top gear kink but still a definite corner. Dittemore was driving. After a couple of runs Jimmy said he just could not get through this kink (as I call it) without lifting 'cause the car definitely wanted to "come around" if he did”.

But Pete Brock, through his time at Shelby, with the challenges involved in developing the Daytona Coupes for the high speed European tracks they were built for, understood downforce and lift, and had built a beautifully clean, and fully functioning spoiler into the rear deck of the Triumph, which sat flush with the bodywork when laying down flat, but which, from the cockpit, could be adjusted to any angle to aid rear downforce. “We set the spoiler up a few degrees and Jim then said the car went through that kink on rails without even a hint of lifting”.

From 68 cars, the little Triumph qualified 39th, despite on-going brake issues and various typical new car niggles. “In the pit lineup, just before the event, Donald Healey came by admiring the car. He told me he had yet to see any racecar that looked as nice and so well proportioned. Good words from a nice man”, recalls a proud Kas.

At race start, Dittemore was tasked with the opening stint. “The race underway with Dittemore up, everything seemed to be good enough that I walked away from the pits to see what the car looked like in the fast left hander, turn one. I'd just been there a few laps and Jimmy came sailing by doing 360 degree spins without the right rear wheel. The wheel had broken right at the stud circle. Fortunately the car stayed flat and just ground to a halt off the track. The bodywork was not even damaged”. The cause was due to the failure of one of the wheels, which were sourced from Chaparral Race Cars, with the centres modified to fit the Triumph stud pattern. It was in the area of the stud circle the wheel failed, flinging the TR-250K into a spin. Ultimately, there was no bodywork damage done, but there was suspension damage sufficient enough that the team withdrew from the race. “I always suspicioned that somewhere in the practice sessions a bang on a curb or a bale had hurt that wheel without the driver even realizing it”.

-

Administrator

After its one and only competition outing, the TR-250K hit the show circuit, kicking off at the Detroit Auto Show. It appeared, as promised, on the cover of Car And Diver April 1968 issue. Following its promotional duties, Pete Brock owned it for a short time, before selling it, where it passed through several owners, and appeared for a time in the Blackhawk Museum, painted red! Then Bill and Pat Hart bought the car, and commissioned Tony Garmey, of Horizon Racing, to restore it back to its Sebring guise, including the application of its Sebring race number; 47. Tony also races the car on occasion for its owners, and really puts it through its paces. And it sounds incredible!

Sadly, the TR-250K remains a one-off. Triumph didn’t pursue the idea of putting it into production. Explains Kas; “Much to our chagrin, the factory took no notice of this cars existence. No inquiries and no interest. We had built a beautiful high performing car from all factory stock components. Stock frame, suspension, gearbox engine etc, and no one seemed to care about this revolutionary car. What a disappointment, for the TR-250K could have been a real production sports car with flair and flash”.

My thanks to Kas Kastner and Tony Garmey for their input in producing this article. All period photos and original Pete Brock design sketches were supplied by Kas Kastner. The two modern photos taken at Horizon Racing were supplied by Tony Garmey. Check out Roaring Season member Tony’s website at: www.horizonracing.com

-

Administrator

Neat bit of footage here about Kas Kastner, plus some track action of the TR-250K with Tony Garmey at the wheel. Just listen to it!

-

So much nicer than the TR7.

-

The TR7 was not accepted then. I was a member of the Triumph Sports Car Club in the early 1970s and I think I was the only one that liked it.Nobody wanted revolutionary

This TR 250-Klooked fantastic then and even better now.

Typical of the Brit car industry then, only wanted to produce stoge

I am reminded of a proverb about some peoples taste, something about casting pearls........................

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote