-

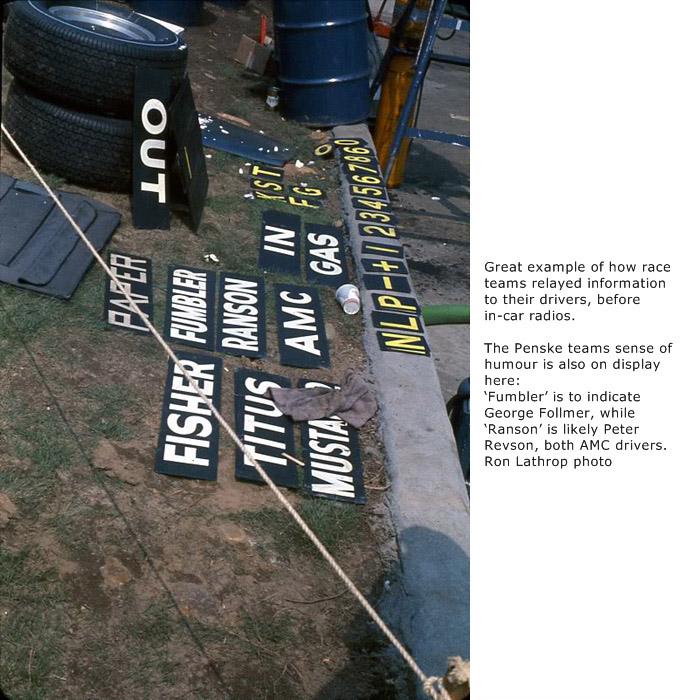

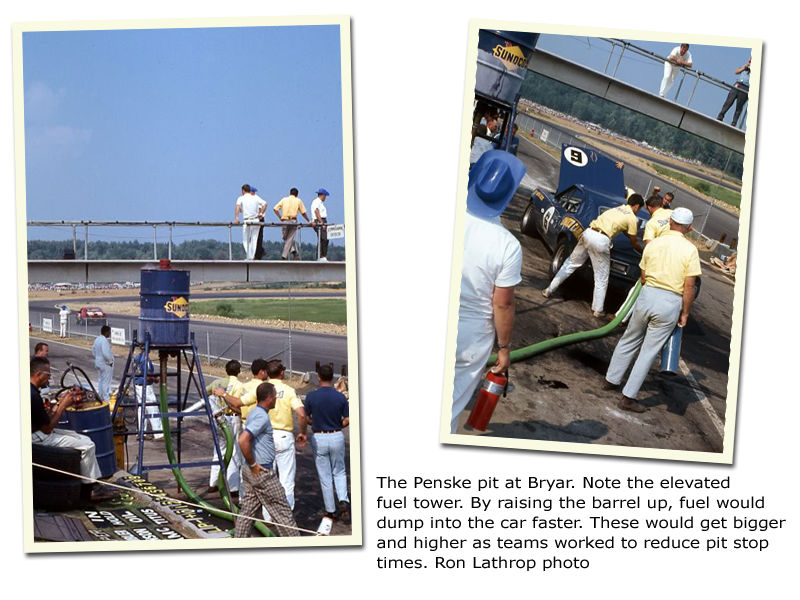

Administrator

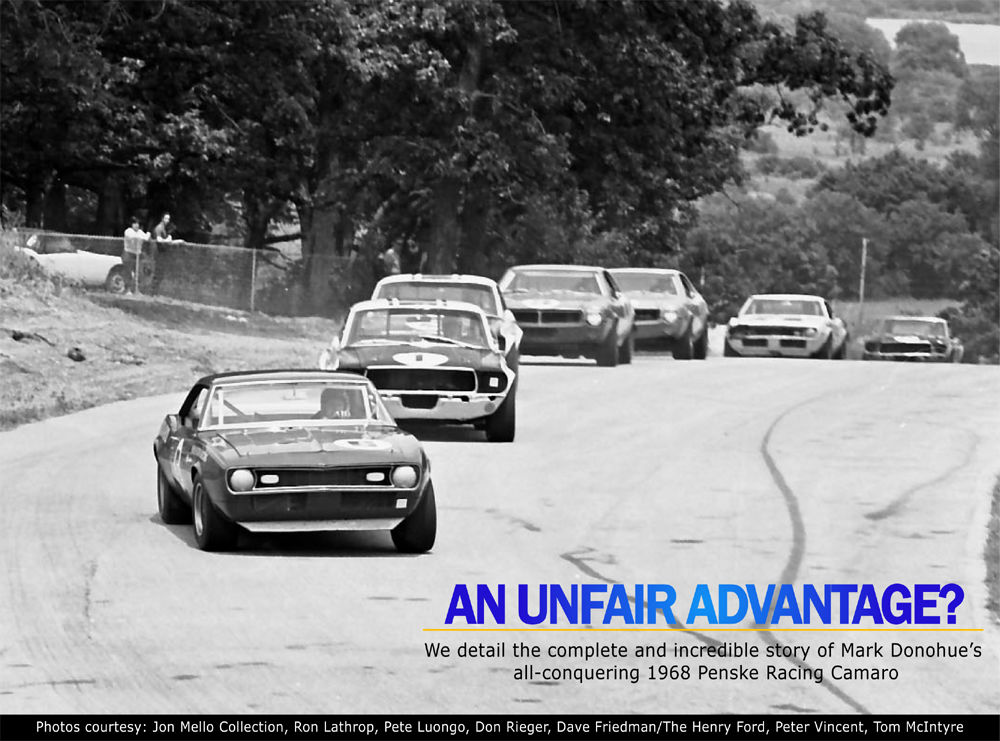

Article: An Unfair Advantage?

“I had only been working full-time in Roger Penske’s shops for a short while when he asked if I’d be interested in putting together a Trans-Am Camaro”, explains Mark Donohue in his book The Unfair Advantage.

Penske and Donohue first met in 1959, but it wasn’t until mid-1966 the pair finally teamed up. Donohue was a mechanical engineer, studying at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. His engineering background drove a natural desire to constantly tinker and improve on the standard fare throughout his motor racing career, venturing further with each new project.

Working his way through the usual myriad of late 1950s/early ‘60s British and American production sports cars and junior single seaters, he won the Sports Car Club of America E/Production Championship in 1961, driving an Elva Courier he’d purchased the year prior. By 1965, he was racing a Shelby GT 350R, owned by Malcolm Starr, sponsor of a Lotus 20 he’d raced in Formula C. With this car he won the SCCA B/Production Northeast Division Championship, gaining him an invitation to contest the American Road Race of Champions run-offs at Daytona. Here he led for much of the race, comfortably outgunning the factory Shelby GT 350R of Jerry Titus until the outside rear tire burst due to the compressed loads of the Daytona banking pressing the bodywork onto the rubber.

For 1966 he picked up a factory ride in endurance sports car racing with Ford’s GT MkII program, running at selected events including Daytona, Sebring, and Le Mans. He and Roger Penske got to talking while at the funeral of close friend, Walt Hansgen, in April 1966. Penske asked Donohue if he’d like to drive his Lola T70 spyder in USRRC and Can-Am events, and Donohue agreed. Penske paid him $50 per day, for each day he worked. At this stage, Donohue held down a full time 9-5 day job. Motor racing was still a weekend hobby for him, despite the intensity with which he attacked it, even then.

The Lola was a battle from the get-go. Given Eric Broadley of Lola Cars was primarily in the business of selling race cars, the exact same T70 chassis could be bought by anyone. So, the Penske guys figured they’d gazump the competition through brute horsepower, and fit the Lola with a big block Chevy, when most others were running small blocks. But, it wasn’t a success. After struggling for much of the year, and wrecking a couple of cars, the team switched to a small block like everyone else. But Donohue had begun questioning his future as a race car driver, and was about ready to call time on his brief career at the end of the season, until Roger Penske convinced him otherwise. He offered Mark a full time position, and rewarded him financially for his efforts. So the Camaro Trans-Am was the first Penske project Donohue had a hand in from the outset.

The SCCA created the Trans-American Sedan Championship in 1966. To be eligible, no less than 1,000 models must have been produced in the last twelve months. The rules were based on those of FIA Groups 1 and 2, although in the Trans-Am they were referred to as A/Sedan and B/Sedan. Classes were then broken up based on engine size: 0 – 2,000cc, and 2,001 – 5,000cc (this later became 0 – 2,500cc and 2,501 – 5,000cc). Maximum wheelbase was 116 inches. Eventually, an 8 inch wheel width limit would be established for the Over-2 cars, as well as a minimum racing weight of 2,800 pounds (1,270 kilograms). As the Trans-Am grew, so interest (both spectator and manufacturer) centred upon the bellowing V8 pony cars as they surfed their boom period of the late ‘60s.

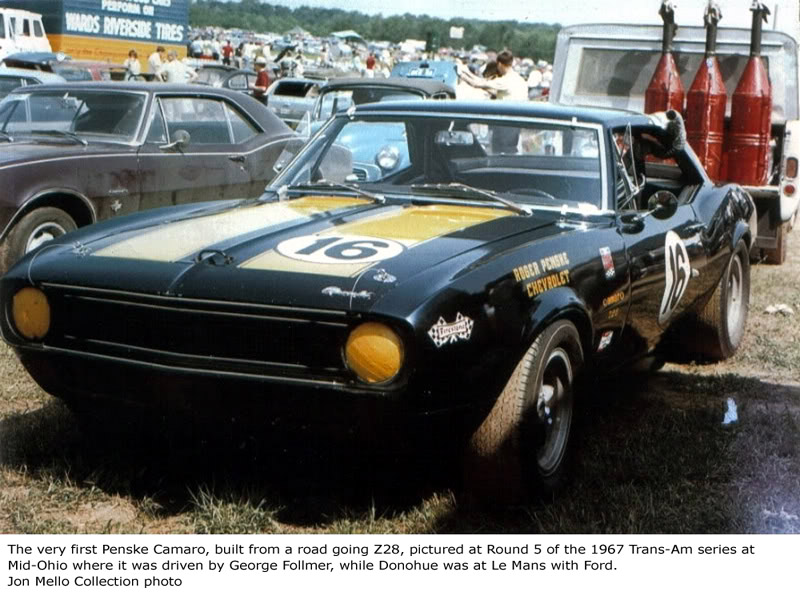

“Roger has always liked to go to the endurance races at Daytona and Sebring. Now, here it was January (1967) and he didn’t have a car to enter”, Donohue explained. A brand new, road going factory red Z28 Camaro was bought, and delivered to the Penske workshop, where Donohue and fellow Penske team member Bill ‘Murph’ Mayberry tore into it. “I had a rough idea what to do with the car to prepare it for racing. In those days there were certain simple basics: install a roll bar, strip the upholstery, fit big tires, and so on. In the meantime, Traco was putting together a 302-inch version of the 333 small block we had been running in the Lola”.

Jim Travers and Frank Coon (Traco was a play on their surnames, TRAvers and COon) built stout power plants, and the team knew they’d have good horsepower, so could focus on race preparing the rest of the car. Given Donohue’s success developing and racing the Shelby GT 350R, Roger Penske assumed his new steed would quickly knock together a world beater, but the new Camaro presented its own challenges, and Donohue found himself swinging in the dark.

“Roger was in touch with the engineers at Chevrolet, and they kept asking him what (suspension) spring rates we were going to use. Then Roger would ask me. But I didn’t want to answer… because I really had no idea. When he saw that I was unsure, he became unsure that I knew what I was doing”. Eventually, Donohue took a punt on 1,200 pound springs in the front, and 400 pound springs in the rear. The car sat very low, virtually on its bump-stops, and also employed the factory Z28 rear axle radius rod. It wore 15” American Racing 5-spoke wheels, wrapped in Firestone rubber. They squirted it in dark blue Sunoco paint (in reference to the teams main sponsor) with yellow stripes, and took it to Bridgehampton for a quick test, where all its ugly traits were revealed.

-

Administrator

With the Camaro being a new car to road racing (remember, Penske were one of the very first to race a Camaro), and Donohue lacking the experience to fully identify its behaviour, he was unsure at first what the problems were, much-less how to fix them. The car bucked and kicked, and the rear axle hopped. But the team had committed to race at Daytona, and they’d be there, no matter what.

The opening Trans-Am race for 1967 was a 300-mile curtain raiser to the Daytona 24 Hour. Several Trans-Am teams ran both races, including Penske. Donohue would drive the Camaro in the Trans-Am race, before switching to a Ford GT MkII for the 24 Hour, with George Wintersteen, Joe Welsh, and Bobby Brown taking over the Camaro for this event. In the 300-mile Trans-Am race, Donohue started behind the factory Shelby Mustangs, but quickly zapped to the front, where he stayed until halted with fuel pick-up problems after 14 of the scheduled 79 laps. The Daytona layout, using part of the oval and a squiggly section of the infield, had done a good job of masking the Camaros various issues, not being a traditional road course. The Traco built motor gave the Penske car more speed on the straights than the Mustangs, and the stiff springs worked well on the high-banks.

The brief debut of the Penske Camaro in the Trans-Am 300 miler failed to expose a tendency to boil its brakes. Instead, this new challenge greeted Donohue at Sebring, Round 2 of the championship, a few weeks later. Again the Trans-Am race, contested over 4 hours, was held prior to the main 12-hour race. “At Sebring we just couldn’t do anything”, said Donohue. “It was the worst handling thing I had ever driven. It was so bad it was beyond belief. It had the same springs we used at Daytona, because we didn’t know any better – and it was just awful. Then the brake problems started to show up, and I crashed it and tore the nose off. I qualified way down (actually, he qualified fifth), and got in the race, but the Fords all ran away from us. The brakes went and we struggled along to finish second after Jerry Titus. At least we survived”.

Putting things in perspective, 60 cars started this race, so qualifying fifth and finishing second was actually pretty good. And Donohue even beat home the second Shelby Mustang of Dick Thompson. But his anguish comes from being comprehensively outrun, not only by Titus, but also by the two new Bud Moore prepared factory Mercury Cougars of Parnelli Jones and Dan Gurney. Furthermore, he was doing it tough. Along a straight, smooth piece of tarmac, the Camaro up and ran like it was shot out of a cannon, but it required major development just about everywhere else.

Round 3 was held at Green Valley, where Donohue battled all the way home for fourth. “Dan Gurney won that race in a Cougar and I was fourth, but what I remember most is getting so exhausted that I didn’t think I could last four hours. It wasn’t like driving a race car at all. The car was so hard to drive I just had to fight it all the way. The worst thing was that I didn’t know what was wrong. I was very unhappy about the whole project”.

Following Green Valley, notable General Motors figures, including Vince Piggins, Gib Hufstader, and Dick Rider got together with the Penske team to try and at least cure the brake problems. Their instrumentation showed there was an issue with hydraulic pressure. But they couldn’t suggest a remedy. At Lime Rock, Donohue finished second to Peter Revson, who was filling in for Dan Gurney in one of the Bud Moore Cougars. But Revson was two laps ahead at the end. George Follmer was tasked with wrestling the Penske Camaro at Mid-Ohio while Donohue was at Le Mans on Ford GT sports car duties. Follmer finished third, three laps behind winner Titus and runner-up David Pearson, the NASCAR star making a rare appearance in a Bud Moore Cougar.

After Mid-Ohio, and with Donohue now back on home turf, General Motors extended an invitation to run the Camaro at their Milford, Michigan proving grounds. They wired it up with their instrumentation, and got Donohue to circulate their giant skid pad, while they downloaded data recording the cars behaviour through different tasks. Although not initially providing the solutions everyone was hoping for, this collaboration, and subsequent visits, would show dividends before the year was up.

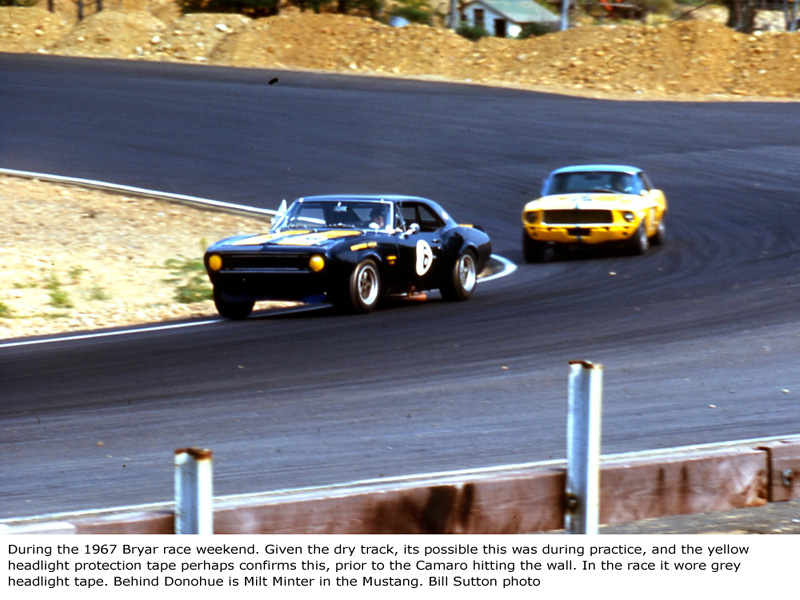

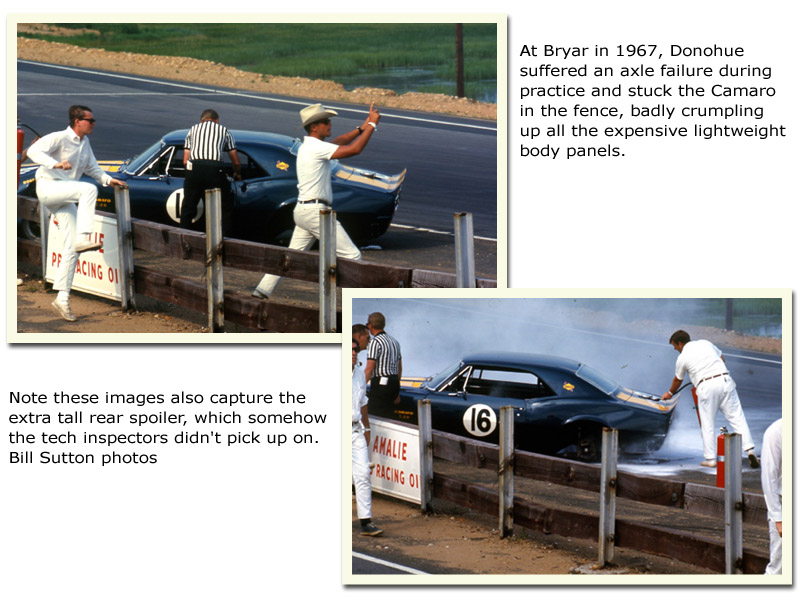

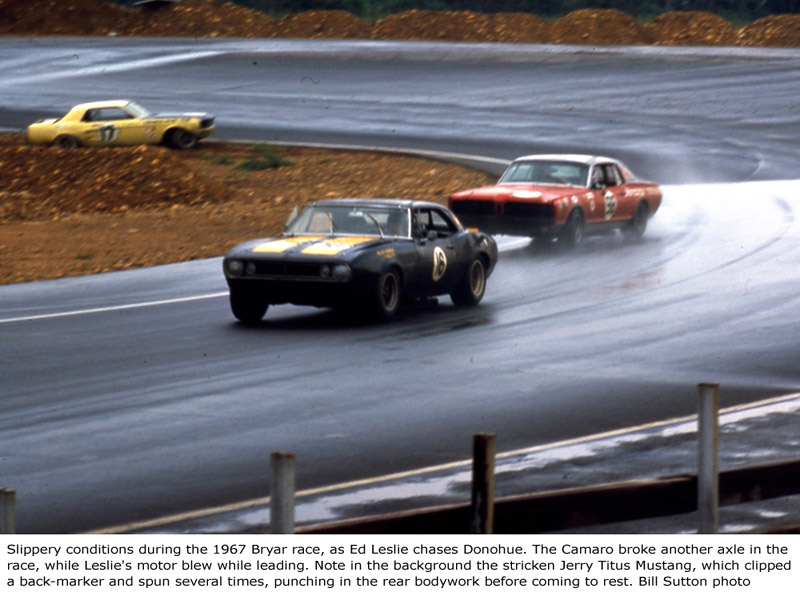

Despite having all the mannerisms of a grizzly bear, with its bad brakes and evil-handling, someone decided the Camaro might benefit if it lost some weight. Shedding a few pounds at this stage was really the cure to a problem that wasn’t a problem, but regardless, a beautiful set of body panels were punched out of thin-gauge steel by Fisher Body, at exorbitant cost. The panels included doors, fenders, hood, and inner-panels. They were fitted up, painted, and then promptly destroyed when a rear axle broke in the Bryar race, and the car was flung into a wall. Roger Penske later discovered his rivals were simply having whole body shells and panels acid dipped, to reduce weight. Acid dipping is, as the name implies, the exercise of dipping metal body parts into a large tank of acid, and leaving them there for a set period of time. The acid then eats away at the metal, reducing its weight. If left for too long, the acid will completely erode the metal, but if done properly, the process can reward with substantial weight savings.

-

Administrator

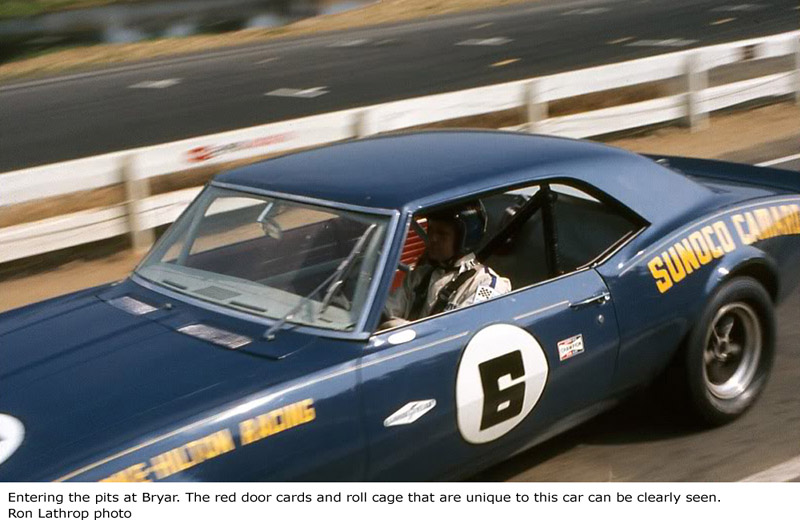

Prior to Bryar, Donohue rightly concluded that a roll cage could serve a greater purpose than simply protecting the driver’s head if the car was ever tipped on its lid. In 1967, most Trans-Am cars were fitted with a simple roll-hoop that ran the width of the car and attached to the floor at four points rearward of the driver. Donohue figured he could use the roll cage to aid chassis rigidity, as was common practice in stock car racing, whereby the cage tubes would connect all four corners of the car. The cage was constructed using steel tubing 1.5 inches in diameter, and .060 inch thick. This action prevented the car from flopping and twisting, and it responded better to chassis set-up changes. Later Penske cars would utilise thinner .040 wall tubing when the Camaro went down the side of a cliff on its way to a race. While the body suffered damage, the beefy cage was unscathed.

Just a single week separated the Bryar race on August 8, and the next round at Marlboro Park Raceway, on August 13, but in that week, great strides were taken. Chevrolet engineer Jim Musser ordered several sets of front and rear springs, and the team arrived early at Marlboro for testing. Vince Piggins had produced new, stronger axles (sadly, about a week too late), and the new springs were tried. Donohue explains: “We started jacking around with all those different springs – and the minute I drove it with the soft springs, I knew everything was going to be alright”. When the Camaro was first built, Donohue settled on spring rates of 1,200 and 400 pounds, front to rear. Testing at Marlboro revealed an optimum 550 front, 180 rear set-up that was less than half what they started out with.

While at Marlboro, they also worked at getting more negative camber into the front wheels (where the tops of the front wheels are closer together than the bottoms, to improve weight transfer and grip levels through cornering), so the outside tire would stand upright through cornering, rather than lay over on its outer edge. Four degrees of negative camber was found to be the optimum, which made steering impossibly heavy, but cornering was vastly improved. Additionally, the rear radius rod was binned, which helped deal with the rear axle hop problem, while Musser produced a rear anti-roll bar, to rid the car of understeer.

The Marlboro round was contested over 300 miles, with each car having two drivers. Donohue teamed up with Craig Fisher. The pair stuck the Camaro on pole, and Penske’s team won their first Trans-Am race, by a full two laps.

Using all the tricks learned to date, an all-new Camaro was constructed to contest the final races in 1967. This was the first car to be acid-dipped, and the team dipped like crazy. So much so, this Camaro would commonly be referred to as the ‘lightweight car’, for obvious reasons. Following the Marlboro win, two more Trans-Am victories were recorded late in 1967, and the Penske team strode off into the off-season with momentum on their side.

For 1968, two all-new Camaros were constructed, using all the knowledge and experience gained during the turbulent 1967 season. Both cars would be cleaner, stronger, faster, more purposeful from the outset, and built for ease of maintenance. The team started not with road cars, as they had done with the first ‘67 car, but with ‘bodies in white’. These were special-order body shells which had been plucked from the Chevrolet assembly line prior to being laden with heavy sound deadener. Sound deadener is fitted to road cars to help muffle out road noise, but in race cars it provides nothing but dead weight. In addition to the two bodies in white that would become race cars, there were between one and three additional bodies supplied to Penske. The bodies and several associated parts were then acid-dipped.

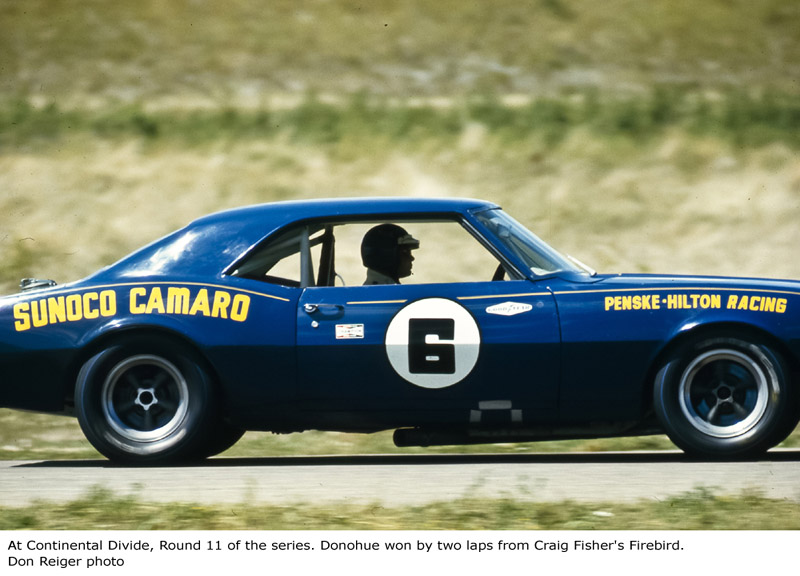

The new cars were blasted in a fresh coat of bright blue paint for sponsor Sunoco. ‘Sunoco Camaro’ was emblazoned along the rear fenders in bold yellow lettering. The cars were works of art. Pin-striping was prevalent throughout, and featured on the hood, the tail pan, and along the hip-line, further enhancing the Camaros curvaceous shape. Large white ‘roundals’ with black borders were applied to the doors and hood. Front chin spoilers wore a contrasting yellow in early rounds, switching to red in later rounds.

Beneath the skin, the Penske machines were just as beautiful. A rigid roll cage connected all four corners of the car. Anything that didn’t serve a purpose was removed. Interiors were sparse, and business-like, with only a race seat, gear shifter, dash, and doors cards contrasting with the clean light-grey paint that filled the cabin. Beneath the hood nestled a Traco built 302 cu.in Chevy, backed by a 4-speed Muncie M22 ‘rockcrusher’, and GM 12-bolt rear-end with limited slip diff. Koni shocks provided the suspending. Brakes were 11.75 inch Corvette discs, while wheels were 15 x 8 inch magnesium American Racing. Partway through the 1967 season, Penske picked up a tire deal, switching from Firestone to Goodyear. It wasn’t just the auto makers and race teams who were at war, Goodyear and Firestone were also engrossed in a battle to produce the best racing tire. Tires were rapidly increasing in grip, durability, and size, and to house the latest king-sized racing boots, the ’68 Penske Camaros featured subtle fender flaring, and custom made wheel tubs in the rear, similar to modern mini-tubs in many road and race cars. Bumpers were removed, as allowed under the rules, to further reduce weight.

-

Administrator

Penske, like all the factory teams, walked a fine-line when interpreting the rule book. In most cases, they worked on the mind-set that anything not clearly stated as illegal, was surely legal. The SCCA were making a slow transition from dealing with weekend warrior amateur racers, as they had done in the past (having been originally established purely for amateur racing), to now dealing with professional teams financed by auto manufacturers, hell-bent on winning at all costs. In cases where rules were specific, the factory teams would go to such lengths as carefully manipulating factory parts to appear stock, when in fact they had been modified. Anything to gain a performance advantage. The Penske crew built clever ‘cheats’ into the ’68 cars, such as moving the control arms, but then modifying the towers, so when going through tech, they still measured as factory stock. Illegal heim-joints were hidden inside the control arms so suspension adjustments could be made.

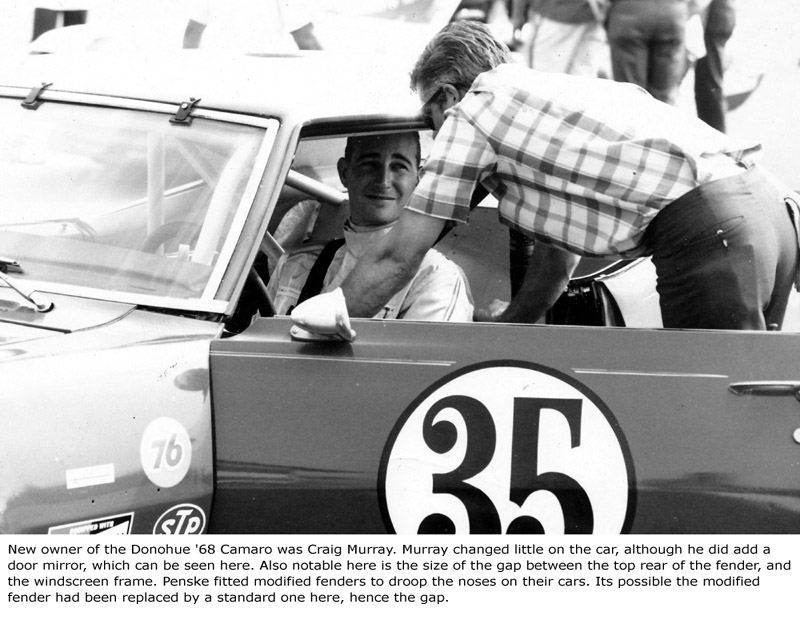

And like the other factory teams, Penske also found ways to ‘massage’ the frontal bodywork to make their Camaros more aerodynamically efficient, while still appearing factory stock. In 1968, most American cars featured a vertical slab frontal area possessing all the aerodynamic qualities of a barn door. At that, Penske crew member Ron Fournier devised a clever tweak to the nose of the two ’68 Sunoco Camaros, slicing at least an inch out of the radiator core support, so he could then ‘droop’ the front sheet metal downwards, thus bringing the nose closer to the ground, creating less frontal drag, and aiding straight line speed. Of course, this trick created the ripple effect of tipping the front fenders forward, leaving a sizable gap between the top rear of the fender and the body cowl, while the lower rear of the fender overlapped the front of the doors. So the fenders also had to be trimmed and/or extended and modified, to appear factory stock. With generous acid dipping, the race weight of the 1968 Penske Camaros was almost bang-on the minimum 2,800 pound Trans-Am race limit. The presentation of the ‘68 Penske cars matched their on-track performances. They were completely flawless.

Unlike the previous year where the build process was a last-minute dash to make the opening event, the first 1968 Camaro to emerge from the Penske workshop was completed with ample time for testing prior to its opening encounter at the ’68 Daytona 24-Hour race. This year, the Trans-Am points race would be part of the 24-Hour race, rather than a curtain raiser a couple of days before-hand.

The team headed for Daytona to get in some early testing, basing themselves in one of Smokey Yunick’s sheds at his infamous Best Damn Garage In Town. They set themselves the target of completing a full 24-hour test run, to gain a thorough understanding of the new car, and iron out any gremlins that might surface during the race. A cylinder head broke during the test, so they replaced it and kept going. They also tried out a new GM dual 4-barrel cross-ram carburettor intake manifold developed by Bill Howell from Chevrolet. The Chevy motors were already the most powerful in the Trans-Am at just over 400 horsepower. The new cross-ram manifold set-up boosted them to around 450, and eventually the Penske Camaros would get up closer to the 475-mark.

The 1968 Daytona 24-Hour began on 3 February, and despite all their confidence, the Penske team were soundly beaten by their Shelby Ford rivals. Penske entered just one car, to be driven by Donohue, Craig Fisher, and Bob Johnson. They qualified 20th overall, and fastest of the Trans-Am cars, two places ahead of the first Shelby Mustang. The Penske Camaro was marginally quicker on track, but the Shelby team were better in the pits. They’d crafted a system for replacing brake pads faster than the Penske crew. In time, the Penske team would build a reputation for their dynamic team tactics and pit stops, but here at Daytona, it was the Shelby crew who emerged looking the smartest. Then, at the 13-hour mark, the Camaro cracked a cylinder head, and several laps were lost replacing it. While the Titus/Bucknum Shelby Mustang won the Trans-Am class, and finished an impressive fourth overall behind a trio of Porsche 907s, the Penske Camaro came home twelfth overall. But they collected points for second in Trans-Am.

Given their single-car effort was blighted by the cracked head at Daytona, Roger Penske opted for a two-car operation at Sebring, employing the old lightweight car from 1967 (the second ’68 car had yet to be completed), now upgraded to look like a ’68. Donohue/Fisher would drive the ’67 lightweight (car #15), while Joe Welch/Bob Johnson drove the new car (#16). Actually, Fisher started and finished the race in the new #16 car but also spelled Donohue in the #15.

-

Administrator

Given their trouncing at the hands of the Shelby team during pit stops at Daytona, Chevrolet’s Bill Howell devised an ingenious system for speeding up brake pad changes. Donohue explains: “The problem (when performing a normal pad change) was that when we slipped the old pads out, the pistons slid out, preventing the new pads from going in easily. The Ford guys had developed some special tools that pushed the pistons back into the calliper, but that took some time also. Bill’s idea was to put a vacuum on the master cylinder to pull the pistons back in. We already had a source, in the brake booster vacuum, so all we needed was a pressure regulator to prevent sucking air in past the pistons, and a valve so that the driver could actuate the system. When we got to Sebring and Roger saw the system, we had to show him that it worked. We jacked the car up in the garage with the engine running to create a vacuum. By the time the wheels were off the pistons had retracted, and the mechanics whipped the old pads out and the new ones in – just like popping bread in a toaster”.

The Donohue/Fisher Penske Camaro was the top qualifying Trans-Am car at Sebring, recording an identical time to the black and gold Smokey Yunick Camaro driven by Al Unser/Lloyd Ruby (but achieving the result earlier in the session) to start 13th overall. Smokey’s Camaro was an early retirement, leaving the Shelby Mustangs as the main challengers, but while there was little to separate the Chevys and Fords on the track, each time they performed a brake pad swap, which was during every second pit stop, or roughly every three hours, the Penske cars would gain a lap on their Ford rivals, so that, after 12 hours, they were four laps ahead of the leading Mustang. Even the second Penske Camaro placed ahead of the lead Mustang, despite issues with its brake vacuum. The Penske team were the darlings of Sebring, finishing a gallant third and fourth overall, behind two factory Porsche 907 sports prototype cars, showcasing just how fast the pony car sedans were, and how professional the Trans-Am teams had become.

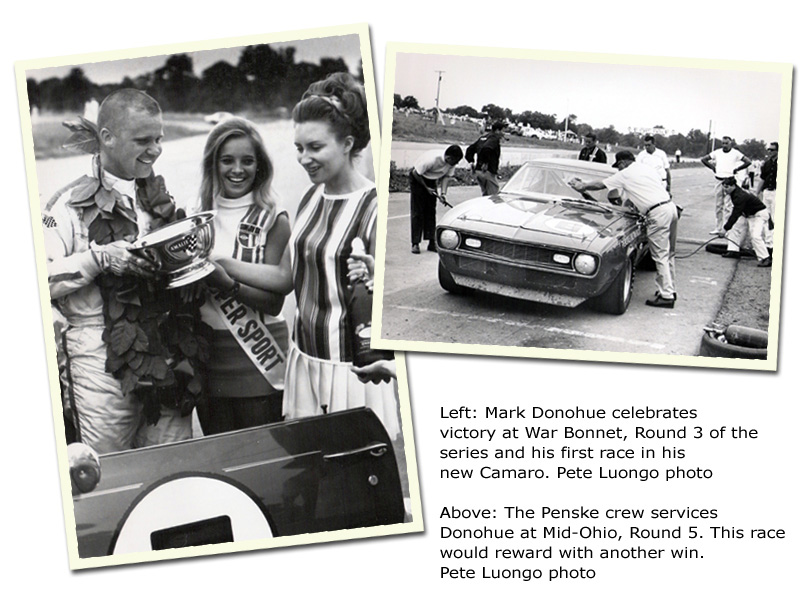

Round 3 of the 1968 Trans-Am series was held at War Bonnet Park, and the race distance reverted back to a shorter 250 mile ‘sprint’ format, requiring just one driver. For this race, Donohue debuted the second new ’68 Penske Camaro built, and the car he would drive throughout the remaining eleven rounds of the championship.

This is our feature car.

At War Bonnet, Penske ran just the one entry. Like the first completed ’68 Penske Camaro, this car was also built from a ‘body in white’. Once again, a fully integrated roll cage was constructed, connecting all four corners of the chassis. This Camaro can easily be identified as having a pair of B-pillar mounted diagonal roll cage bars crossing through one-another in the centre of the car, forming an “X”, and for its red door cards. With this car, Donohue would demolish the opposition throughout the remainder of the championship.

The War Bonnet event typified how much of the 1968 Trans-Am would pan out. Donohue took pole position, and won comfortably. His closest rival at the end was George Follmer in one of the new Ron Kaplan prepared AMC Javelins. War Bonnet also saw the debut in the Trans-Am of the new tunnel-port 302 cu.in motors fitted to the Shelby Mustangs. In an effort to bridge the horsepower gap enjoyed by Penske and other Chevy teams, Ford developed their trick new tunnel-port motors, in which the pushrods were housed in tubes that ran through the intake ports (hence the name), allowing the ports to take a more direct route from the manifold to the cylinders, as they didn’t need to curve around the pushrods. These heads provided larger intake valves and less restriction. But while powerful, they would also prove chronically unreliable.

At Lime Rock, Round 4, Donohue again started on the pole, and won handily, taking victory over Titus by two laps. At Mid-Ohio, the Penske team set themselves a new challenge, missing qualifying while Donohue was away at Mosport Park racing an Indy Car. No problem. He started the race off the back of the grid, was leading by lap 10, and won by a lap from Titus.

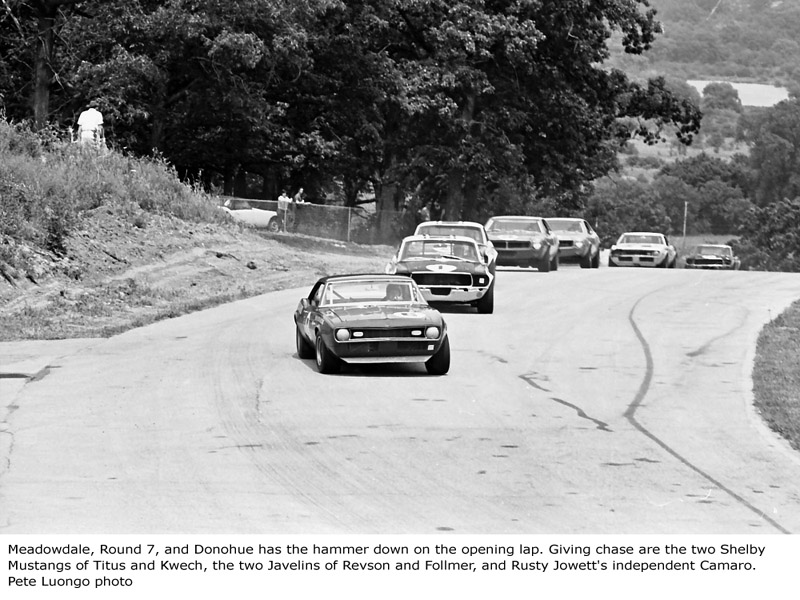

For Bridgehampton, the Sunoco Camaro program expanded to two cars, with Sam Posey putting together a deal with Roger Penske to drive the car raced earlier in the year at Daytona and Sebring. Posey finished the race in third, behind George Follmer’s Javelin, and race winner Donohue, who also took pole. At Meadowdale, the results were the same, only it was Peter Revson who split the Sunoco Camaros this time around, in his Javelin. Donohue then beat Follmer and Posey at St. Jovite. Here he was a lap ahead of the second placed Javelin.

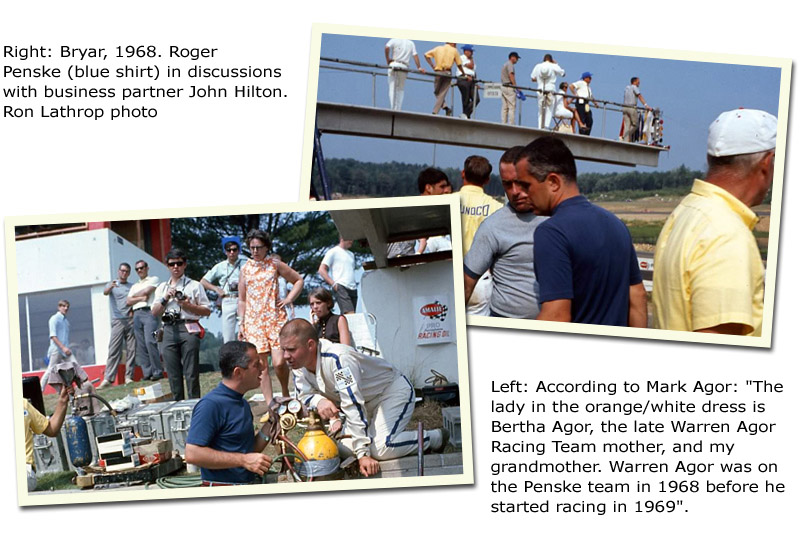

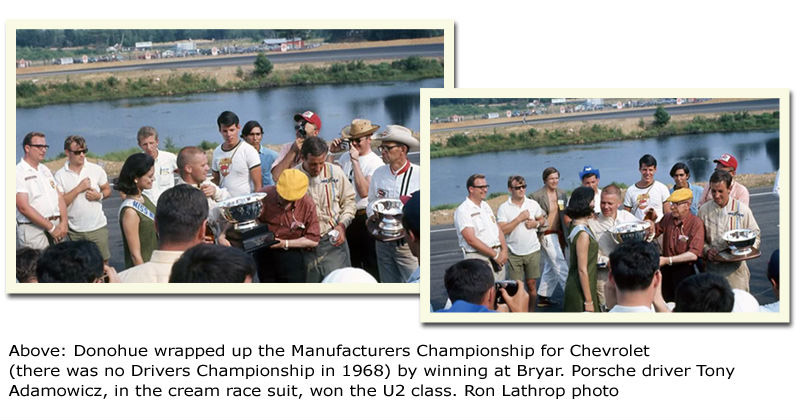

At Bryar, Donohue was finally knocked off the pole, if only just, by Titus, but when the chequered flag waved after 125 laps, it was the blue Camaro that blazed across the line in front. In fact, it was four laps in front. Penske only brought one Camaro to Bryar, with Posey returning for the next race at Watkins Glen.

-

Administrator

Round 10 of the Trans-Am championship was notable, for being the first race since the season opener at Daytona which wasn’t won by a Penske Camaro. Titus took victory here, from Posey, and Donohue. Different publications have offered different explanations on why Donohue was off his game. Some say it was because he was ill. Donohue himself wrote, in The Unfair Advantage, it was because he’d used up his brakes. But regardless, he couldn’t challenge Titus. But Posey could. He led much of the race before running out of fuel. After pitting for a top-up, he charged off after Titus once more, moving ahead, until flat-spotting his tires avoiding Rusty Jowett’s gyrating Camaro. Rather than have his car rattle itself to pieces with badly flat-spotted tires, or risk a blow-out, he went screeching into the pits to have new wheels and tires fitted, but in 1968, there were no driver-to-pit radios, and his team were unprepared for his arrival. Frazzled, they eventually fitted new rubber, and he set off again in search of Titus, but the Mustang driver was still in front at the finish.

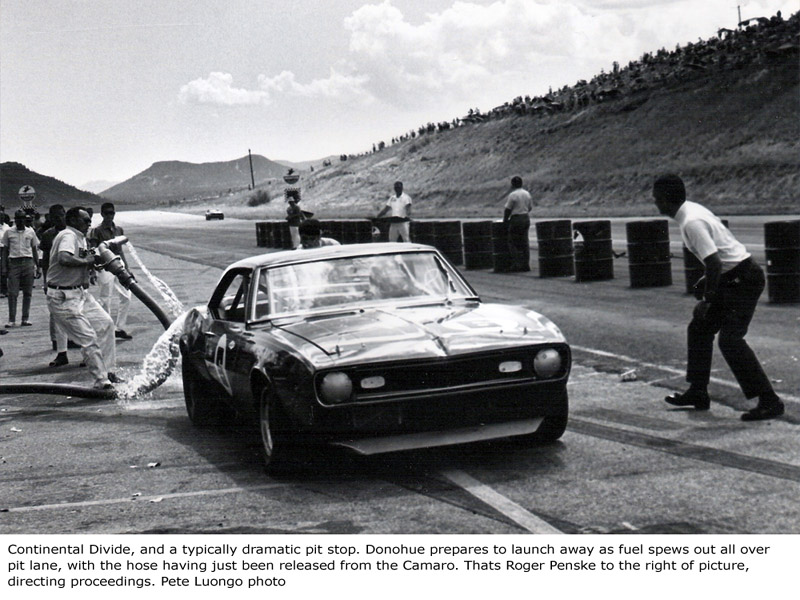

Roger Penske opted to run just one car for the remaining three races. At Continental Divide, normal service resumed, and Donohue took the win. A rare engine failure ended his Riverside race after 61 of the scheduled 96 laps, but Donohue took a commanding victory in the final at Kent, after battling the early laps with Titus, who’d switched camps to drive a Terry Godsall run Chevy powered Pontiac Firebird. Titus also took the pole, but broke an engine after 43 laps.

For the Penske team, the 1968 Trans-Am had been one of total dominance, winning ten out of thirteen races, and placing second in two others. And they did so against full factory backed teams of Ford Mustangs, and AMC Javelins, as well as several cashed-up independent operations, including that of Canadian Godsall, which, in partnership with Titus, would go on to run the factory Pontiac program in 1969.

Donohue’s main race car, that which first appeared in Round 3 at War Bonnet, won nine of the eleven races it contested. The Penske team blew the doors off the opposition with an impressive display of speed and reliability. Donohue was at one with his machine, spending so much time with it, building, testing, and racing, that he was as intimate with his race car as any driver could possibly be. The Penske operation was the epitome of professionalism and slick organisation. All the hard work was done back at the shop, and in testing. The cars were completely torn down between races, repainted, and reassembled with almost everything replaced or refurbished. While other teams scrambled to perform engine, transmission, or rear-end swaps at the track, the Penske team showed up with their gleaming blue rocket-ships, the crew donning fresh clean uniforms, and then they smoked everyone in qualifying and the race. It looked effortless. Of course, it wasn’t, but that was part of the ploy. The Penske team had the opposition on the ropes before they even rolled their cars off the trailer.

Certainly, Penske’s dominant display in 1968 left their rivals reeling. Auto manufacturers only get involved in the racing game to sell more cars. All their silver-tongued ad-men and catchy slogans have little use if their cars are getting beat-up on every weekend by the competition. Motor racing is marketing, and has a dollar value. Of the 13 Trans-Am races held in 1968, Camaro took 11 wins, Ford 2, and AMC 0. Who do you think got the most marketing mileage out the season? Ironically, General Motors still had their self-imposed ‘no-racing’ policy in place, officially, at least.

Sales of Fords Mustang dropped from 472,000 units in 1967 to 317,000 in 1968. Meanwhile, Camaro sales grew from 221,000 in 1967 to 235,000 in 1968. A good portion of that customer loyalty and growth could be attributed to the familiar sight of Mark Donohue and his gleaming blue racer with the yellow ‘Sunoco Camaro’ lettering emblazoned down its flanks storming to victory, race after race.

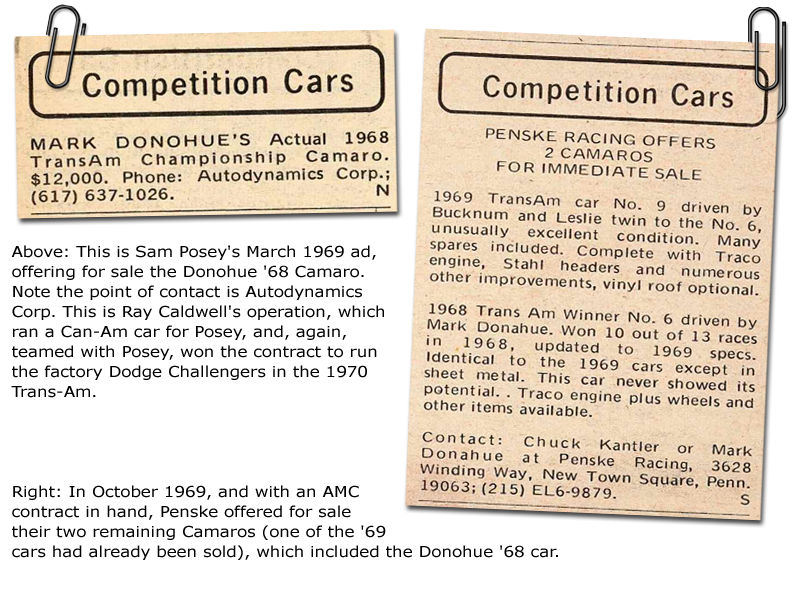

The Sunoco Camaro domination in 1968 forced their rivals to greatly improve their performances in 1969, and each of the factory outfits built completely new race cars, including Penske, who stepped up to run a full-time two-car operation. Two new ’69 Camaros were constructed, for Donohue and new Penske signing, Ronnie Bucknum. As part of his arrangement with Roger Penske for 1968, Sam Posey paid for and took possession of one of the ’68 cars. Curiously, rather than the car he himself drove, he instead ended up with Donohue’s car. Posey placed a classified for the Camaro in early 1969, trying to off-load it for $12,000, but failed to find a buyer.

Meanwhile, Penske tore into 1969 with their two new cars, up against four (and sometimes five) factory Mustangs, run by Shelby and Bud Moore, plus factory Firebirds and Javelins. After a slow start, the Penske team were well in control by mid-season, but with so much at stake, so the level of intensity, paranoia, protesting and counter-protesting between rival factory teams quickly escalated. When Goodyear-contracted Donohue employed under-handed tactics to get hold of and evaluate the latest Ford-contracted super-trick Firestone tires, so the animosity rose further, and it was Jim Musser from Chevrolet who strongly urged employing the services of a back-up car, should Ford choose to retaliate, and sacrifice one of their cars to escort Donohue far off into the scenery.

-

Administrator

With Donohue’s ’68 car gathering dust at Sam Posey’s (Posey himself had a one-off drive for Shelby in 1969, and won!), Penske bought the car back, and mechanically upgraded it to 1969 spec (but retaining the ’68 body), installing a new motor, new paint, front and rear bumpers (new Trans-Am rules for 1969 required bumpers) and replaced the American Racing wheels for yellow painted Minilites, which the team were using on their ’69 cars. But fortunately for Penske, its services weren’t required, and at the end of the season, with Penske signing a lucrative new deal to run the factory Javelin’s for 1970, the three team cars were moved on to new owners.

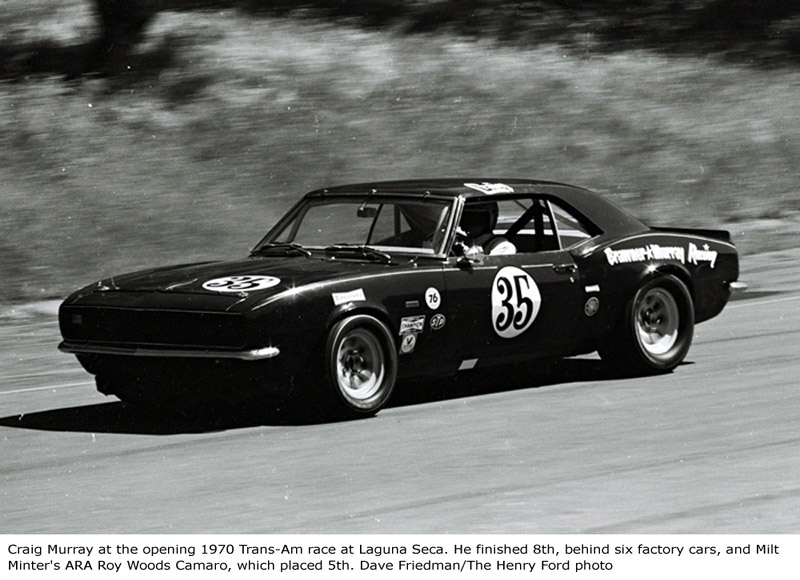

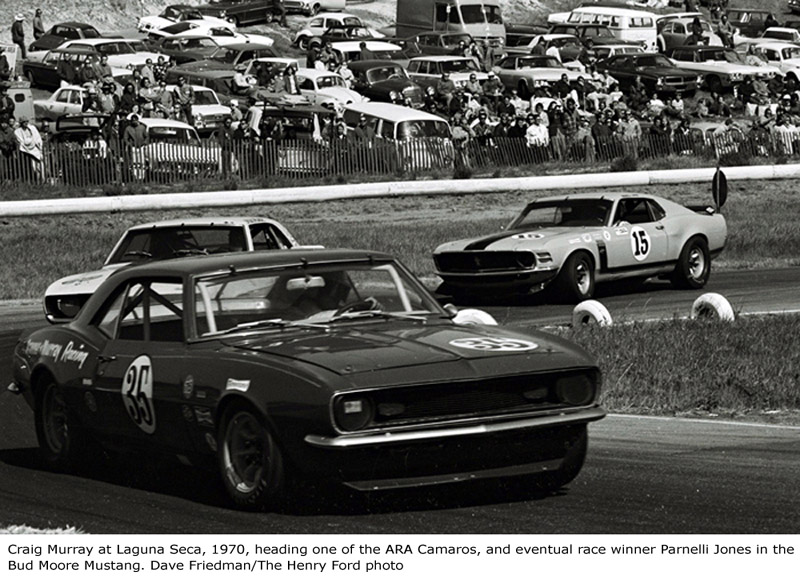

The 1968 Donohue Camaro was purchased by Craig Murray, President of the recently opened (1968) Sears Point Raceway (now Sonoma Raceway). Murray had only just gained his competition licence in early 1969, and spent much of that year racing an MG Midget in various West Coast production sports car events, before purchasing the Camaro. He changed nothing, other than adding a wing mirror, which none of the Penske cars were fitted with, and changed the race number from Donohue’s #6, to #35. He then raced the car at selected Trans-Am events in 1970, recording a best finish of eighth at Laguna Seca. He also entered local West Coast A/Sedan races, plus a USAC Stock Car race at Laguna Seca. The USAC event marked the first appearance in Northern California for USAC Stock Cars, and the first USAC event to combine stock cars and pony cars. Murray finished the race in fourth, behind a pair of Plymouth Road Runner Superbirds (which placed first and third), and another Camaro.

Throughout the 1970s, after Craig Murray’s ownership, the Camaro changed hands several times, moving to John Elder in Minnesota, before it was purchased by Bruce Belcher in Idaho, and then Bill Freeman in California. At the time of purchase, Freeman was in the process of teaming up with Paul Newman, establishing Newman-Freeman Racing. They bought a Porsche 911 RSR, and the Camaro was sold once more, to Bob Eckhardt, also in California, who raced it twice in IMSA events at Ontario and Riverside.

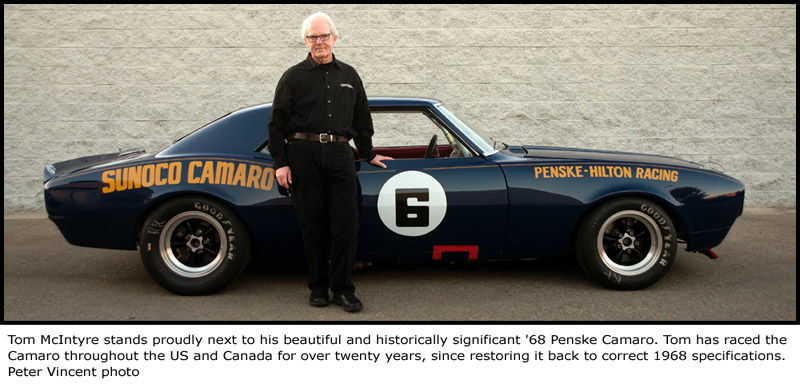

Sedan racing changed beyond all recognition during the 1970s. The SCCA’s three big professional road racing series’, the Trans-Am, Can-Am, and Formula A each either faded or failed altogether, while former SCCA executive director and creator of the Trans-Am series, John Bishop, launched the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA) in the early ‘70s, which quickly rose to prominence as the most important professional road racing sedan championship in the US. As if to confirm acceptance of this, the SCCA changed their Trans-Am rules to mimic those of IMSA (who themselves were using FIA European Groups 1 to 4 rules, plus their own home-grown All-American GT), which allowed for huge aluminum engines, big wheels and tires, massive flares, and even tube-frame chassis’. With such change taking place, many of the old original Trans-Am cars were either chopped up and modified heavily to keep pace, or simply retired, and, in some cases, scrapped altogether. But not so the Mark Donohue ‘68 Penske Camaro. Somehow, the Camaro snuck right through the crazy, hazy ‘70s virtually unscathed and untampered with. Even the Sunoco blue paint and yellow Minilite wheels remained intact, until the car was purchased off Eckhardt by Tom McIntyre in the early 1980s. Tom still owns the Camaro to this day.

Recognising the cars enormous historical significance, and the growing interest in early Trans-Am race cars, Tom spent several years restoring the Camaro back to its 1968 guise, finally returning it to the track once more in 1993. Its first event was at Sonoma, formerly Sears Point, the race track at which Craig Murray once presided. The level to which the Camaro has been restored is stunning, and accurate in every way, right down to the application of red tape beneath the doors to indicate where the Penske crew members were to shove their jacks as they belted out one of their furious Trans-Am pit stops.

Tom is one of the leading-lights in the ever-growing Historic Trans-Am group, the most popular group in vintage racing for cars that competed in the Trans-Am series from 1966-1972. Interest in Historic Trans-Am is huge, with cars being added all the time. Since that first event in 1993, Tom has raced his beautiful Penske Camaro all over the US and Canada.

Fittingly, a chance meeting would bring Tom and Craig Murray together, and the pair have remained friends ever since. Tom explains; “Following the 1969 season, Penske sold all three of their Camaros (the pair of ’69 cars and the updated Donohue ’68) with the ’68 car going to Craig Murray, the President of Sears Point Raceway. Well, thirty years later I was under the car cleaning up something and I hear this man say to his Grandson, “Well look at this… Your Grandpa once had a race car just like this one”. I nearly banged my head on the underside of the car as I said, ”Your name wouldn’t be Craig Murray would it?” Sure enough, that lucky day I found the man who bought the ’68 Camaro from Penske.

“We spent the next two hours talking and telling all the stories of who, what, where, when and why he did what he did with the car. It was amazing to see the glow as he told these stories”. Over the years Tom has met and spoken to all the prior owners of the Camaro, hearing their stories and seeing their photos, with each one explaining their time with the car and the success they had with it. As with any historic race car, half the fun in owning it is joining the timeline dots together that make up its full history.

-

Administrator

This particular Camaro remained the most winning single chassis in all of Trans-Am racing until 1992. In 1968, it entered eleven races and won nine of them during a period of immense manufacturer involvement and intense competition. It is a legend among legends.

Mark Donohue referred to Penske’s exceptional performances in racing as their ‘Unfair Advantage’. But what did he actually mean by this? What exactly is an unfair advantage? The term itself suggests an advantage gained through unfair or unjust means. But of course, this was not its intended use, not in this setting. A more accurate description of the term, and surely that to which Donohue applied it, would be this: ‘To gain an unfair advantage, is to do everything just a little bit better than your competition’. Certainly, these were the fundamentals to which Mark Donohue applied himself until the day he died, and to which Penske Racing apply themselves to this day. And, of course, they’re the fundamentals to which this very special race car was built. It was just a little bit faster than the competition at most tracks. It was also more reliable, and stronger. And Penske Racing were often just that bit better in the pits.

And so, to that end, did Penske Racing enjoy an unfair advantage in the 1968 Trans-Am? Yes, indeed they did! Mark Donohue’s summary of that ‘68 championship was typically understated, but, reading between the lines, it’s clear this was a season from which he drew enormous satisfaction: “Sometimes it seems as if we spent entire seasons just putting bandages on bleeding sores”, he said, “but that year we were really looking good”. It’s rare in any racers career to have a season like the one Donohue and Penske Racing enjoyed in 1968. They hit the ground running, kept the throttle hard open, and never relented.

Thanks to Tom McIntyre, Jon Mello for their help with this article.

-

Administrator

This is a story taken from Issue 1 of Muscle Car Digital Magazine: www.musclecardigitalmagazine.com

-

Fantastic article - thanks Steve

-

-

Administrator

Thanks guys, I really appreciate that.

-

In my humble opinion it came down to a superior brake set up.

The Camaro had the little original disc/drum combo removed and they specially fitted the proven massive 12 inch vented Corvette 4 pot Delco Moraine disc set up front and back, And by the way you cannot just bolt them on the back, you need the correct rear end. And GM had that all ready to go as they already had this set up on the Corvette.

This gave them a huge advantage,that no one else had.

Spencer Black imported a big block Camaro with this rear set up on and fitted it into the Team Cambridge Camaro improving its performance.

Norm Beechey was able to fit them to the front of his Monaro,- once again GM parts bin.

Just my view, not detracting from Penskes professionalism.

Last edited by John McKechnie; 03-25-2016 at 06:08 AM.

-

Semi-Pro Racer

Love the article Steve....bought back many lost memories to me.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote